The Exorcist didn’t just help kick off the Seventies horror boom, it also kicked off a Catholic horror boom. After the film adaptation came out in 1973, priests, crosses, and communion chalices suddenly crowded the horror paperback racks. Between 1974 and 1983, you couldn’t escape red-eyed demonic priests with Satanic smiles staring out at you from the bookstore shelves. But tucked away behind all this strutting Catholic iconography lurked a smaller genre — Jewish horror.

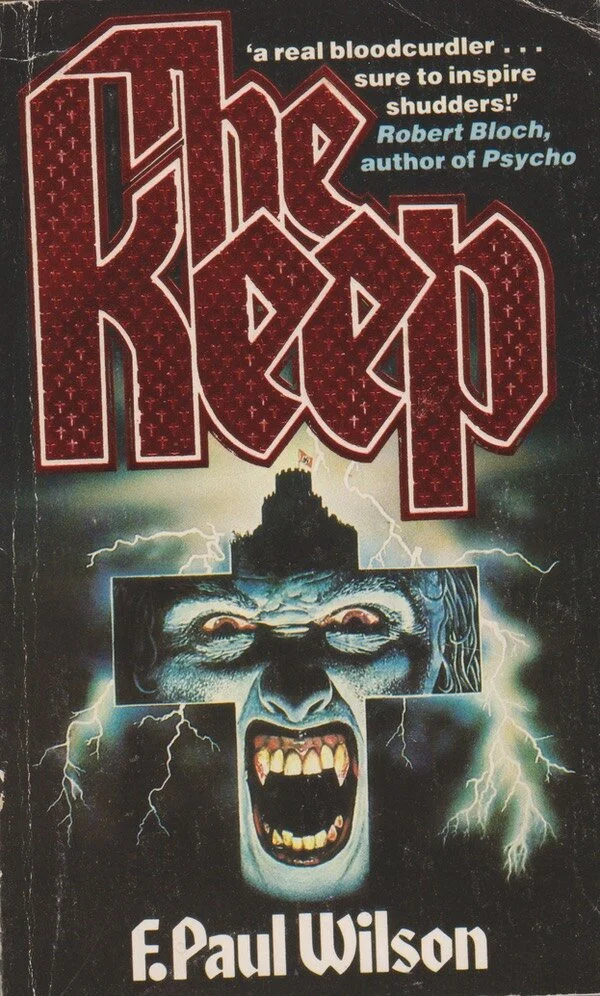

Later books like Red Devil (1989) and The Gilgul (1990) used Jewish folklore and religious iconography to tell horror stories, but the genre made its bow at the height of the Catholic horror boom, courtesy of Bari Wood’s The Tribe (1981) and F. Paul Wilson’s The Keep (1981). The Tribe is a modern retelling of the legend of the Golem of Prague, whereas Wilson’s The Keep deals with Judaism more obliquely and in the guise of the big, fat, international thrillers authors like Robert Ludlum were popularizing in the early Eighties. A swaggering, World War II adventure story full of warring immortals, sneering Gestapo officers, magic swords, and Weighty Questions about Faith, The Keep arrived as the smaller novels of the Seventies started giving way to the massive blockbusters of the Eighties. Painted in broad strokes on a big canvas, The Keep fits comfortably into a decade that would make literary rock stars out of authors like Anne Rice and Stephen King.

Author F. Paul Wilson had already written a handful of sci-fi novels, but his first love was horror. He just didn’t see a big enough market for it. Then, in 1975, he read ’Salem’s Lot.

“I got it through the Literary Guild,” he says, naming the massive mail order book club that circulated hundreds of thousands of copies of mostly mainstream fiction to American readers. “They didn’t mention it was horror on the jacket copy, and you didn’t see the word ‘vampire’ anywhere, so I thought it sounded like an interesting mystery with some darker elements. I remember reading it and thinking ‘This sounds like a vampire, but they’re going to cop out at the end.’ And then it turns out to be a vampire. What really stuck out to me was the scene in Mark, the kid’s, room and he has all those Aurora model horror kits — Frankenstein, the Mummy, the Wolfman — and I built those same models as a kid. I didn’t know who this Stephen King guy was, but I knew right then that he was one of us. And somehow, he’d managed to get his vampire book into the Literary Guild. That’s when I knew it was going to be okay. I could write my horror novel now.”

Wilson’s agent, Albert Zuckerman, counted Ken Follett (Pillars of the Earth, Eye of the Needle) among his clients and he knew the value of a big book. He’d sold Wilson’s sci-fi books for a few thousand here and a few thousand there, but now he asked his client to pitch bigger novels with higher stakes. Wilson had recently read Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Hotel Transylvania (1978) and he found her idea of a good vampire ridiculous. “They’re parasites,” he says. “You really have to bend over backwards to make them good.” But what if something pretended to be a good vampire to hide the fact that it was much, much worse?

He set his book in the past because the market was filling up with ’Salem’s Lot knock-offs that dragged ancient vampires into modern settings and, because he wanted to balance his supernatural evil with human evil, World War II made sense. “Everything was swirling around in my head,” he says. “And I had this vision of a keep studded with crosses, which of course makes you think of vampires, and so I put it in the Transylvania Alps on the eve of World War II, but something was missing. I knew they weren’t crosses, they had to mean something else because I wanted to get away from the Catholic connotations, and then I realized they were the hilt of a sword, and the book just came together.”

Wilson gave three outlines to Zuckerman, who told him there was something to the one about the castle in Romania, and he started to write. A practicing physician, Wilson spent all day composing his work in his head, then at night he’d sit down and write three pages. It took him nine months to deliver the first draft of The Keep. Even though it was King and Yarbro who provided his initial inspiration, three other authors served as his guides: Robert Ludlum, Robert E. Howard, and H.P. Lovecraft.

Wilson had read Ludlum’s The Scarlatti Inheritance and been blown away by its intricacies.

“I wanted it to be different from the other horror novels coming out,” Wilson says. “I wanted it to be an international thriller like a Ludlum novel, because you can never trust anyone in a Ludlum novel.” And in The Keep, Wilson made sure that every single one of his characters, like a spy, lied to themselves or lied to each other as they pursued their secret agendas.

The Lovecraft influence came from the idea that what happened in the book would only be one dimly perceived battlefield in a vast, cosmic war that had been raging for eternity. Whether it’s Glenn (real name Glaeken), the eternal warrior for the forces of light, or Rasalom, an ancient sorcerer who’s impersonating a vampire, the characters in the book are merely pawns. Wilson borrowed Lovecraft’s concept of vast, inhuman forces that are indifferent to mankind, but he didn’t name them because, as he puts it, “The second you name Cthulhu and describe what he looks like you’re taking the first step on a road that ends with Cthulhu plush toys.”

Wilson’s problem, however, was that faced with cosmic forces of antipathy and hate, most of Lovecraft’s protagonists either crawl into a corner and die, or go mad. He wanted his heroes to stand up and fight, and that’s how he came to Robert E. Howard.

“Howard had the same type of mythology as Lovecraft, he even shared some of Lovecraft’s gods,” Wilson says. “But whereas in Lovecraft the hero always surrendered to darkness or madness, the Howard hero realized they were outmatched but they preferred to go down fighting. That’s the approach I like.”

Wilson sent his first draft to Zuckerman and went away for the weekend. When he returned there were six messages from his agent: Zuckerman was thrilled. The two of them edited it together, and for Wilson it became a crash course. A hands-on agent, Zuckerman showed him how to weed out passive voice from his manuscript, confronting every “is” or “was” with, “Find a better verb.” For Wilson, a self-taught writer, Zuckerman’s feedback felt like a revelation. Every publisher who read the manuscript wanted it, and they sold the movie rights to Kirkwood-Koch Productions before they sold the publication rights to William Morrow, who brought out the hardcover in August, 1981, where it did...okay.

But when Berkley brought out the paperback, it popped up on the New York Times bestseller list almost immediately and stayed there for two weeks. Because of its European setting, it sold numerous foreign territories (sixteen at last count), and Wilson, after getting a false start on another book, went on to write The Tomb in 1984, the first of his Repairman Jack books (twenty books and counting), another New York Times paperback bestseller.

Kirkwood-Koch, meanwhile, had a deal with CBS Theatrical Films and they brought in Michael Mann (Heat, Miami Vice) as the writer and director. Unfortunately, CBS’s gamble on a Sally Field-Tommy Lee Jones blue collar rom com, Back Roads (1981), bombed, and The Keep went into turnaround. Paramount brought it out of motion picture limbo and Mann developed the screenplay. Wilson read it and thought a lot was missing, but his worries were assuaged when he visited the set at Britain’s Shepperton Studio and watched them shooting a scene that seemed right out of the book. His relief lasted until he attended a screening in New York City two days before the movie opened in 1983.

“That’s when I realized what a mess it was,” he says. “It was upsetting. I’d had high hopes that the movie would be a success because that opens up doors for your other books, but it was such a horrendous failure, critically and financially, that people started thinking of me as the guy who wrote that turkey. No one in Hollywood reads, so they assumed the movie and the book are the same thing.”

But there were two bright sides. Enough people bought the movie tie-in edition to push total sales of the novel over one million. “That’s because the few people who saw the movie didn’t know what the hell was going on so they went out and bought the book to try to figure it out,” Wilson says. And, over the years, The Keep has become a cult classic, treasured by fans for its off-kilter special effects, Mann’s stylish direction, and its spare, synth-heavy Tangerine Dream soundtrack. The movie has garnered so many fans that a feature-length documentary about its making is in the works. Its source material, on the other hand, endured not as a cult hit, but as a real hit.

“Out of all my backlist,” Wilson says. “It’s still the bestseller. The Tomb is a close second, but The Keep has always been number one.”

What’s kept this book alive owes nothing to Lovecraft, Howard, or Ludlum, or even to Yarbro or King. What brings The Keep to life comes directly from Wilson’s own experience. As a fifth grader at a Catholic school, he’d watch Christopher Lee back away from the cross in a film, and he couldn’t understand.

“A lot of my friends were Jewish,” he says. “And you see this depiction of ultimate evil helpless before the cross, and I’d always think, ‘What do they think of that?’ In Judaism, you’re supposed to be waiting for the messiah, but the cross is a sign that the messiah has already come, and I always wondered what it must be like to be a Jewish kid and read Dracula and see your entire faith called into question.”

The Keep gave Wilson a chance to put this question to his characters, and the crisis of faith that Professor Cuza suffers is excruciating and personal. Worse, however, is the presence of another cosmic evil: the Holocaust. The Keep is a book that layers supernatural evil — a sorcerer, serving dark forces, pretending to be a vampire — with increasingly extreme human evil — Jewish civilians, confronted by a good German soldier who serves his fatherland, who is confronted in turn by a Gestapo officer who embraces The Final Solution — but it also literalizes Lovecraft’s cosmic horror through the horrors of genocide. When Woermann, the good German soldier, Professor Cuza, and his daughter Magda learn of the scale and scope of the coming Holocaust, as death camps are built and train lines are laid and blueprints are drawn and human industry and ingenuity are applied to mass murder, they are staggered, shocked, left speechless and impotent, much like Lovecraft’s characters when confronted with the enormity of cosmic horror. Rasalom’s plan to turn the entire planet into a concentration camp feels like a literal embodiment of the infinite despair heralded by Lovecraft’s Elder Gods.

“Rasalom, as I have told you, feeds on human debasement,” Glenn tells Magda. “And never in the history of humankind has there been such a glut of it as there is today in Eastern Europe...But he’ll not be satisfied. He’ll want more...soon all will be in chaos. And then the real horror will begin. Think of the entire world as a death camp!...People will be born into misery; they will spend their days in despair; they will die in agony. Generation after generation, all suffering to feed Rasalom...And the worst of it all, Magda, is that there will be no hope. And no end to it.”

And finally there’s Glaeken, an exile, sole survivor of a long vanished civilization, living in a strange land, whose ancient knowledge connects him to a primordial source of power and goodness. Even though he’s not Jewish, given that backstory, it’s hard not to picture him as a swashbuckling, Jewish warrior when reading The Keep. But the book’s real hero is authentically Jewish: Professor Cuza’s daughter, Magda. Raised to be her father’s helpmeet, she eventually stands up to him, to the Nazis and to Rasalom himself. There were barely any female characters in Robert Ludlum’s fiction, so having a young Jewish woman wind up being the bravest character in this book guaranteed that The Keep stood out from the pack.

And while Wilson’s The Keep will always serve up big screen heroics and horror with an epic sweep, it’s the character of Magda, so atypical for its time, Professor Cuza’s crisis of faith, and the literal embodiment of Lovecraft’s cosmic evil in the mechanics of the Holocaust, that have made The Keep such a compelling, thorny, barbed book that’s lodged itself inside readers’ minds, and in their hands, for almost 40 years.

A version of this essay appears in the Polish edition of THE KEEP from In Rock/Vesper press.